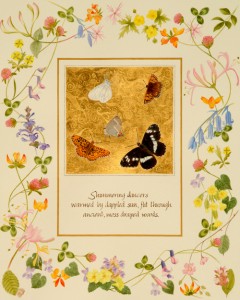

Gilding – attaching gold leaf to paper

24 carat hand scrolled gold, shell gold, acrylic and ink on paper. This piece was inspired by medieval manuscripts and shows endangered butterflies surrounded by the plants they need to survive. The verse is in the form of a Japanese haiku with 5-7-5 syllables.

The richly illuminated borders and miniatures of medieval manuscripts are a delight. They vary in design and complexity, and change with changing fashions, but there is nothing to surpass the dance of light on highly burnished gold.

Not all manuscripts were gilded. Gold leaf was comparatively rarely used before 1200. It is difficult to handle, being thinner than the thinnest paper and almost without weight. It blows away with the merest breath, to ruffle or fold upon itself. As many manuscript painters worked in monastic cloisters open to the wind, trying to manipulate gold under those conditions must have been endlessly frustrating (and resulted in a lot of wasted gold!). After this date, most manuscript work was done indoors, making gilding conditions more favourable.

Flat gilded areas are achieved by sticking the gold onto paper with a solution called a ‘mordant’. There are several of these recorded. Cennini, for example, writing in 1437, describes the use of garlic, with ‘bulbs taken to the volume of two or three porringers’, ground in a mortar and strained through a linen cloth. To this mixture he added white lead and a red clay called bole. Other possible adhesives are ‘size’, made with an animal skin glue, egg white, and various gums. We have information on the preparation of gum ammoniac – a gun-resin exuded from the stem of a perennial herb, Dorema ammoniacum – from De Arte Illuminandi, a 14th century manuscript.

The mordant is applied to the paper and allowed to dry. Breathing on the area reactivates it enough to make it sticky – gold leaf is then applied and pressed firmly onto the surface.

Tooling

Basically, anything with a point can be used to make a mark on the gold leaf. One made, the mark can never be erased, and if too close together, the gold between has a tendency to fall off, so the technique is not without its pitfalls. However, it can add interest to an otherwise flat area, giving a beautiful contrast between the textured and smooth.