Furness Abbey lies, abandoned in rain-drenched seclusion, in a valley in southern Cumbria. A vast expanse of red sandstone, it’s ruined now, of course. Some of the large church is still standing, but you can see the crack running up one of the walls. And you can’t ignore the feat of modern engineering that is holding it all up. But somehow it doesn’t detract from the atmosphere especially when, on a bleak winter’s day, you have the place to yourself. In the silence, if you stand still, you can imagine the shuffle of monks’ shoes and almost feel them brushing past you on the way up to the high altar.

Furness Abbey was founded in the early twelfth century, when the Church had immense power and wealth.

The land was given to the monks by Stephen, who was to become king of England in 1135. The Abbey rose to become the second richest Cistercian monastery in England, after Fountains Abbey in Yorkshire. At its height it ruled over 55,000 acres, possessing both extensive forests and rich farmland. It owned iron mines, salt pans and, believe it or not, oyster beds.

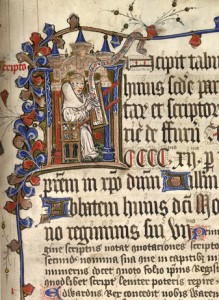

This is a page from the cartulary of Furness Abbey, a collection of deeds and charters. The scribe who wrote it in 1412 slipped his self-portrait in – what a great way to be remembered! Photo: British Library

As the rain drips off my snug, waterproof mac, I can’t help wondering what it might have been like to live here. I presume there were paths, once, rather than grass and mud – much less wet on the feet. But it must have been cold, especially during a Cumbrian winter.

There were hearths in the kitchen, but warmth elsewhere was a later addition. On display in the visitor centre there is a medieval cresset lamp, made of sandstone –

The hollowed out cups would have been filled with oil and have wicks floating in them, producing a flickering light, but I can’t help thinking that monks rose early and went to bed as the day’s light faded.

One of the Abbey’s most important assets was the stream of Beckansgill, providing fresh water.

The fact that the kitchen was downstream of the reredorter or latrine may have made the large infirmary building necessary….

On a brighter note, no trip out is complete without a quick sketch. You can see the results of this on-site work at the bottom of this post. This is me, bundled up in two fleeces and a mac, in a brief respite from the rain, sketching in the Chapter House.

The monks used to meet daily in this room for confession and to hear a chapter read from the Rule of St. Benedict (hence the name chapter house).

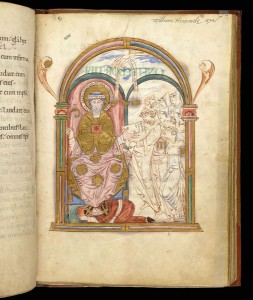

St. Benedict from the Arundel Psalter, produced in Canterbury, England, between 1012 – 1023. Photo: British Library

Monks slept in dormitories. They ate in the great frater, another large building measuring some 150 feet long, sitting on raised benches at tables. Simple vegetarian food was served and eaten in silence, except for one the voice of a single monk who would stand in the pulpit and read a passage from scripture. I hope they warmed something up for him afterwards….

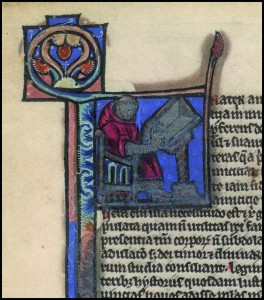

Monk reading. Taken from a Bible (Harley 2813) produced in Oxford in 2nd quarter of the 13th century. Photo: British Library

The wealth and power of the Abbey didn’t last. The combination of raids from Scotland, famine, plaque and war with France badly affected the Cistercian economy, and Furness found itself in financial difficulties. The final blow, however, was Henry VIIIs measures to bring the church under control. The last abbot, Roger Pyle, gave up the Abbey and its possessions to the King, making Furness the first of the major monasteries to be dissolved in 1537. Lead was stripped from the roof and the buildings were dismantled while the monks still lived there.

It is now owned by English Heritage. There’s a well written guide book and an indoor display of stone carving, including some effigies of knights. No café, but there is a coffee machine which provides a decent drink and welcome warmth on a chilly winter day. Allow plenty of time – it’s a big site and full of interest.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks